I. Introduction

The word “Bible” comes from the Greek word biblia (βιβλία), which means “books” or, more literally, “scrolls.” A scroll is a long sheet of papyrus rolled up to the middle. The Bible is a collection of small ‘books’ or writings that originally circulated independently on scrolls, but were later collected into a single volume after the invention of the codex (pages bound together along one edge like a modern book).

The Christian Bible is made up of two main parts called the Old Testament and the New Testament respectively. What most Protestants call the Old Testament is a collection of books also considered sacred in Jewish communities of faith, although its contents are arranged differently. For Jewish communities, the Bible is made up of 24 books arranged into three sections: Torah (Instruction, or Teaching), Neviim (Prophets), and Kethuvim (Writings). Using the first letter of the Hebrew names of these three divisions, Jewish communities call this collection the Tanak (T-N-K). Since virtually all of the Tanak/Old Testament was written in Hebrew, many scholars use the neutral term Hebrew Bible when referring to these books.

The Old Testament used by Catholics, Eastern Orthodox Christians, and a few Protestant groups contains six or seven books (plus some additions to the books of Esther and Daniel) that are not found in the Jewish Tanak or the Bibles used by most Protestants. These additions are found in the earliest known Greek translations of the Hebrew Bible, but not among the Hebrew documents that were eventually adopted by Jewish communities as the Tanak. In many modern translations of the Bible these additional books are included in a special section called the Deuterocanon by those groups that consider them scripture and the Apocrypha by groups that do not.

II. What is in the Hebrew Bible?

While the first seven books of the bible appear in the same order in both Jewish and Christian bibles, the rest of the Hebrew Bible is organized quite differently in the two faith traditions. Let’s now take a brief look at the contents of each of the three main sections of the Hebrew Bible as used in Jewish communities.

A. Torah

The Torah, often called the Pentateuch by Christians, consists of the first five books of the Bible (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy). The term torah is used more broadly to mean all of God’s instruction or revelation, but when used as the title of a specific section of the Hebrew Bible, it refers to these first five books.

Many English translations render the Hebrew word torah as law. But these books tell the story of the formation of the people of Israel. “Law” is not a very helpful title here. Perhaps we should translate torah as teaching in this case since much of the Torah is story rather than rules.

The story begins in Genesis with what we might call prehistory—the story from creation to the emergence the ancestors of Israel. It continues by telling the story of those ancestors up to the time of Moses, the greatest leader of Israel’s early history (and arguably, of all of Israel’s history). Moses leads the people out of captivity in Egypt, and encounters God at Mount Sinai where they receive God’s Law. They then wander in the wilderness for forty years at the end of which they are on the edge of the land that God has promised them, and there Moses dies.

The books of Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers gather together almost all of Israel’s oldest legal material and religious customs. The setting is the experience with God at Mount Sinai. Much of this same material is recapitulated in the book of Deuteronomy, which ends the Torah.

B. Prophets (Neviim)

The section of the Tanak called the Prophets consists of two main parts. The Former Prophets (Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings) are often called history in Christian bibles. These books tell the story of Israel from the death of Moses through the occupation of Canaan (the promised land), the rise of the Kingdom of Israel (under David and Solomon), the division of that kingdom into the nations of Judah in the South and Israel in the North, the conquest of the northern kingdom by the Assyrians, and finally the conquest of Judah (the southern kingdom) by the Babylonians. This story is told from the perspective of the religious traditions reflected in the Torah, especially in the book of Deuteronomy. For that reason these books are sometimes referred to by scholars as the Deuteronomic or Deuteronomistic History.

The Latter Prophets consist of Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel (called the major prophets by Christians) and the Scroll of the Twelve (called the minor prophets by Christians). This section is very different in form from the Former Prophets. Rather than being in the form of a story, these books are collections of the words of Israel’s prophets who lived between the eighth and fifth centuries BCE (799-400 BCE). Much of the material in these books is poetry rather than the prose style found in the Former Prophets. Still, these books do include some short anecdotes about the prophets written in prose.

C. Writings (Kethuvim)

The section called the Writings contains a diverse collection of documents in several different literary types. Psalms, Lamentations, and the Song of Songs (Song of Solomon) are poetry. Proverbs is a collection of conventional wisdom sayings. Job and Ecclesiastes also come from Israel’s wisdom tradition, but they represent challenges to the conventional wisdom.

Chronicles, Ezra, and Nehemiah are history interpreted in light of Israel’s religious values, much like the Former Prophets. Perhaps for that reason these books are placed immediately after 2 Kings in Christian bibles.

Ruth and Esther are short stories. They do not say much about God, but are important stories that interpret significant values of the Jewish people. (Hauer and Young call them ‘edifying fiction.’) They are included along with Song of Songs, Ecclesiastes, and Lamentations in the Megilloth, a collection of five festival scrolls to be read at important religious holidays.

Daniel is the only example of an apocalyptic work in the Tanak. Apocalyptic was an influential literary form that arose after the Babylonian conquest of Judah. It tended to be used in times when people were experiencing significant persecution, and it uses vivid imagery and striking symbolism. [The book of Revelation in the New Testament is the only other full-length apocalyptic work in the Christian bible.] Christians later came to see the book of Daniel as prophetic, and it is placed among the prophets in Christian Bibles, but it was not classified among the prophets in ancient Israel.

III. What is in the Apocrypha / Deuterocanon?

Like the Writings, the deuterocanonical books are a diverse collection of documents. Ecclesiasticus and Wisdom of Solomon are wisdom books like Proverbs, Ecclesiastes and Job in the Hebrew Bible. The two books of Maccabees interpret part of the history of the period between the last writings of the Hebrew Bible and the first writings of the New Testament. Tobit and Judith are short stories. Susanna and Bel and the Dragon are short stories added to the book of Daniel. The Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Young Men are poetry added to Daniel. The Deuterocanon also contains some additions to the book of Esther which emphasize conventional piety.

IV. What is in the New Testament?

The New Testament—written entirely in Greek rather than Hebrew—begins with a collection of four Gospels. These documents tell the story of Jesus’ ministry, death, and resurrection. Within this narrative framework many of the teachings of Jesus are also included. They have the double aim (1) of encouraging their readers to become followers of Jesus and (2) of teaching those who have already done so.

Like the gospels, the Acts of the Apostles tells a story. It takes up where the gospels leave off (with a resurrection appearance of Jesus) and gives an overview of the early spread of Christianity from Jerusalem to Rome. The author tells this story as the work of the Holy Spirit through the followers of the resurrected Jesus.

Most of the remainder of the New Testament consists of letters. While some of these documents are anonymous, most are connected in some way with the ministry of one of the earliest church leaders. Thirteen of them bear the name of Paul. Even some documents that may have originally been sermons or essays eventually became regarded as letters because this literary form was so popular (Hebrews, James, First John).

The New Testament Ends with the Revelation to John, the only full-length apocalyptic work in the New Testament.

V. Conclusion

The focus of this web site is on the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament. We will take a quick look at the Apocrypha/Deuterocanon and some of the issues it raises, but most of our discussion of the Hebrew Bible will focus on the books accepted by both Jewish and Christian communities. Because of the size of the Hebrew Bible we will spend more time there than in the New Testament. We will contrast the arrangement of books of the Hebrew Bible in the Tanak (the Bible of the Jewish communities) with the arrangement in the Old Testament (of the Christian communities).

In discussing the New Testament, we will look at how it influences the way Christians read the Hebrew Bible and at the role of the early church in selecting the documents that would become the second part of the Christian Bible.

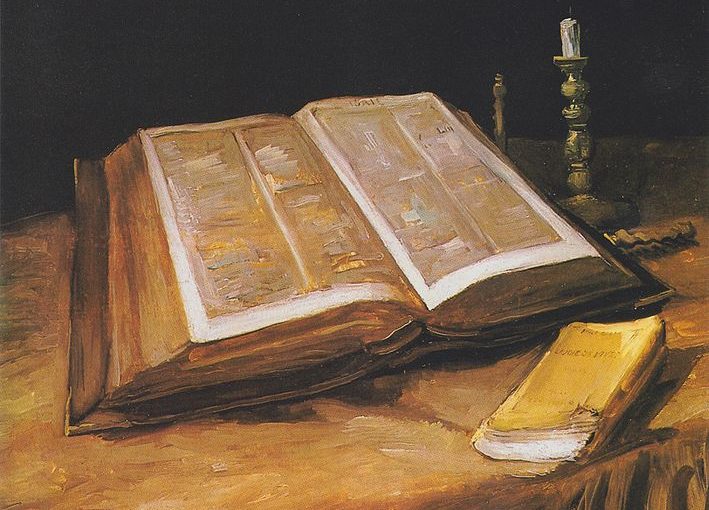

Photo credit: The featured image at the top of this page is a photograph of Vincent Van Gogh’s, Still leben mit Bibel (Still Life with Bible). The image is in the public domain in the United States, and is taken from Wikimedia Commons.

One thought on “Contents of the Bible”