Let us now turn our attention to the stories about Abraham and Sarah and the first few generations of the ancestors of the nation of Israel found in chapters 12—50. We will first examine the contents and literary structure of those stories, then look at what scholars have said about the historical period in which they are set. The literary structure of these stories is easier to establish than the relationship of the stories to otherwise attested history. No ancient documents from the relevant time period besides the Bible make any direct reference to the characters discussed in these stories, and this section of Genesis makes no reference to any event that can be documented elsewhere. Still, the stories have enormous value for the communities of faith that regard them as scripture.

Unlike Genesis 1—11, which I have called the prehistory, Genesis 12—50 discuss a period in which writing could conceivably have existed, but there is no evidence of Hebrew writing this early. While these stories could conceivably be based in part on some kind of formalized summaries, this material was transmitted from generation to generation in oral form long before it was structured into the written narrative that we have today.

Several of the characters mentioned in these stories have eponymous names, that is, names from which the names of later places or people are thought to have derived. Jacob has his name changed to Israel, for example, and the later nation of his descendants would be called by that same name. His sons have the names of the later tribes of the nation of Israel. The story in which these characters appear is told from a decidedly pro-Israelite point of view. Still, the story acknowledges many of the failings of the ancestors of Israel in a way uncharacteristic of other ancient near eastern literature.

Genesis 12—50 constitutes a saga—a long story following the lives of one family from the distant past over several generations. This saga begins with the journeys of Abram and Sarai, later called Abraham and Sarah (Genesis 12—25), continues with the intertwined stories of Isaac and Rebekah and their son Jacob with his wives Rachel and Leah (25—36), and ends with the adventures of Joseph (37—50), first in Canaan, then in Egypt.

The main theme of these chapters is God’s promise to Abraham and his descendants to make them a nation (12:2), protect them (bless them: 12:3), and give them a land (12:7). This promise is repeated several times. The idea of naming provides a parallel theme. A name represented one’s reputation or destiny. Abram, Sarai, and Jacob will all receive new names in this story. The story is about God molding the destiny of Abram and Sarai and their descendants, and about the struggle of these people with the new destiny assigned to them.

The literary motif of journey furnishes the main structure for the narrative. Journey is a common feature of ancient epic literature. In this story the ancestors of Israel travel, and it is on their journey that the promise is repeated, endangered, and reaffirmed several times and that their life in relation to God is transformed. Abraham travels to Canaan; Jacob goes to Paddan-aram and returns; Joseph and his family go to Egypt. In the remainder of the Torah (Exodus—Deuteronomy), Moses will travel to Midian and back, and the people of Israel will travel out of Egypt, through the wilderness to the edge of Canaan.

The Roles of Women in the Narrative

The nomadic society of Israel’s origins relegated women to a subservient role as did other societies in the region, but it allowed them a stronger role than they would be assigned later by the male-dominated political systems that would arise in the Mediterranean world. As you read these stories, notice the ways Sarah, Hagar, Rebekah, Rachel and Leah contribute to the development of the theme of promise. In contrast to most of the women mentioned later, these women have spoken roles in the story.

The Abraham and Sarah Cycle (Genesis 12—25)

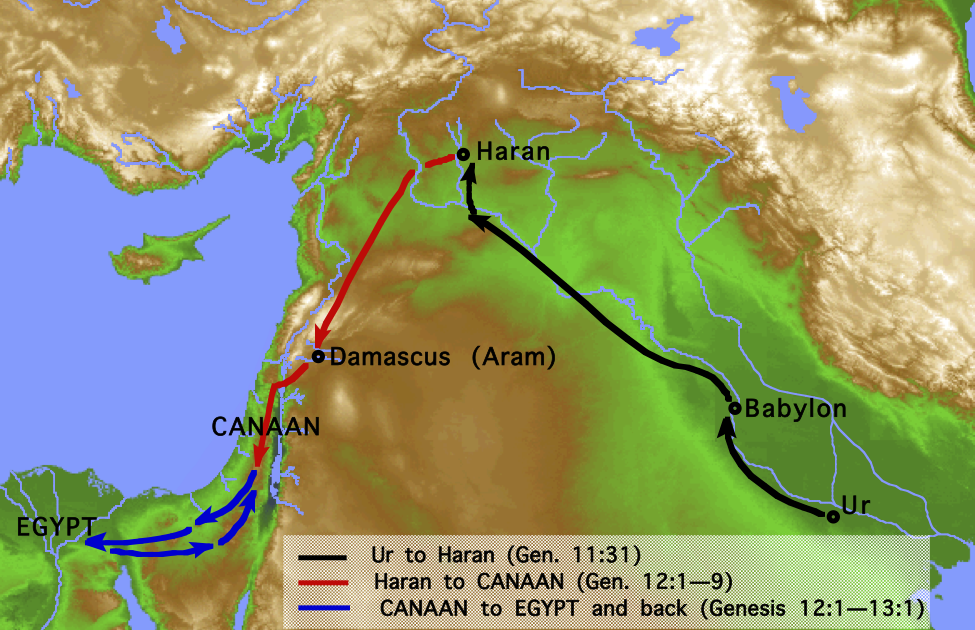

The end of chapter 11 tells of Abram’s father, Terah moving the family from Ur (in southern Mesopotamia) to Haran (in northern Mesopotamia). It is in Haran that God’s promise to Abraham will first be introduced.

| Map Work | Find Ur and Haran on the map below. Mesopotamia is not labeled on that map. Where does it belong? Judging from what you have read so far, could you label Mesopotamia on the map without looking back at the maps presented earlier? |

|---|

Read Genesis 12:1—3. What does God promise Abram here?

The Lord said to Abram, ‘Go from your country, your kin, and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. 2 I will make you a great nation, and I will bless you, and make your name great, and your name will be a blessing. 3 I will bless those who bless you and curse whoever curses you; and in you all the families of the earth will be blessed.

The promise of a nation creates a tension that helps advance the story: the reader has already been told in 11:30 that Sarai (Sarah) is barren. Despite the apparent absurdity of the promise, Abram obeys the command to leave his family and land to follow the Lord’s direction.

| From this point forward I will adopt the usual practice of representing the divine name “Yahweh” as “the Lord.” |

Characterization of Abraham, “the Father of the Nation”

Since Abraham would be remembered as the “father of the nation”, his characterization in these stories is significant. The narrative develops Abraham’s character by showing the reader his actions, not telling of his thoughts. This is typical of ancient stories. We see that he is faithful (following the Lord’s command), resourceful (though somewhat devious: 12:10—20), financially successful (13:2), a successful negotiator/mediator (chapter 13: the separation of Abram and Lot), and a military hero (chapter 14).

The characteristic that plays the most prominent role in the narrative is Abraham’s willingness to trust the Lord. When God tells him to leave his ancestral homeland and his family ties, he does so without question (12:4). Later God promises to be his protector (15:1) and when Abram complains that he has no heir, God reaffirms his promise to make him the father of a great nation (15:2—5). Abram accepts the promise without further question, and God views this as the act of a righteous man (15:6).

Abram put his faith/trust in the Lord, who reckoned it as righteousness (15:6).

Abram’s decision to trust God, relying on God rather than his own skill to insure the future of the promise, contrasts sharply with the attempts of earlier generations (in the stories of communal origins) to become independent of God. Adam and Eve eat the fruit of the tree of knowledge so they will be able to make their own judgments about good and evil; the people of Babel build a tower so as to insure their own access to God. A righteous act—according to this narrative—is one that acknowledges dependence upon God. Abram trusts Yahweh to make a name for him (שֵׁם 12:2, compare the Tower of Babel story).

Still, it should be observed that at some points in the story Abram does question God’s promise. In 15:8 he asks about the land that Yahweh has promised, “O Lord God, how can I know that I shall possess it?” Abram’s questioning is not presented as a lack of faith, though, but serves as the prompt for the covenant that God establishes with him later in the chapter. God’s promise to Abram is sealed with a covenant (15:18) after the Lord accepts his faith (15:6). A covenant ceremony is performed in response to Abram’s request for assurance (15:8).

| The form of the covenant ceremony described in this story seems bizarre to many modern readers. It is probably intended to represent the form of a ritual of self-condemnation. It implies that God—represented by the smoking fire pot and the flaming torch (15:17)—wishes upon himself the same fate as the sacrificial victims if he fails to fulfill his promise. |

Chapter 16 contains the story of Hagar and the birth of Abraham’s first son, Ishmael. We will return to that story below.

The promise is repeated in chapter 17, but the scene is slightly different. God calls himself El Shaddai (אֵ֣ל שַׁדַּ֔י 17:2 usually translated “God Almighty”) and instates circumcision as the sign of the covenant (17:10—12). The covenant is made with Abram and his descendants. El Shaddai will be their God and give them the land of Canaan as an eternal holding (17:8). God repeats the promise of a coming son, but Abram—now called Abraham—laughs at the possibility of having a child in his old age (17:17). Again in chapter 18 the promise is repeated. This time the Lord speaks in the presence of Sarah as well, and she laughs just as Abraham had done earlier (18:12—15).

From Abram and Sarai to Abraham and Sarah: the Importance of Names

Abram’s name is changed to Abraham (17:5) and Sarai’s name is changed to Sarah (17:15). The importance of “a name” (שֵׁם) has already been established in the preceding narrative. When Yahweh changes the name of Abram to Abraham and Sarai to Sarah, he is asserting, or assigning a new identity as well as a purpose and a destiny.

| Names | Abram means “Great Father,” and Abraham means “Father of many.” Both Sarai and Sarah are derived from a verb (שָׂרָה) meaning “persist,” “struggle,” “exert oneself,” or “overcome.” The name of the later nation of Israel is based on this same verb. |

|---|

Abraham, Lot, and the “Cities of the Plain” (18:16—19:29)

In chapter 18 the LORD tells Abraham about his plan to destroy the city of Sodom—the city where Abraham’s cousin, Lot lives—and Gomorrah, its neighbor. Abraham negotiates with Yahweh on behalf of the cities. He asks if Yahweh intends to “sweep away the righteous with the wicked” (18:23) and convinces God to spare the cities if even ten righteous people can be found there.

In the drama that follows, two angels arrive in Sodom and are hosted by Lot. That night “all the people to the last man” surround Lot’s house and demand that he send out the two guests (not knowing that they are angels). The men outside the door say they want to “know” Lot’s guests. “Know,” in classical Hebrew, was a euphemism for sexual activity. The men outside the door intended to rape Lot’s guests, as is clearly indicated by Lot’s response. Lot pleads with them not to act so “wickedly” (19:7). He offers his own daughters to the men instead. They refuse and demand to be given the “men” inside. The angels now intervene, striking the men outside blind, so that they and Lot’s family can escape.

This story is often cited as a condemnation of homosexuality, but it is interesting that the story does not make an issue of the homosexual nature of the intended crime, but seems more concerned with violation of hospitality customs. When Lot offers to let them rape his daughters he does so because “these men have come under the shelter of my roof” (19:8). Lot is willing to see his daughters raped rather than violate his obligations as a host.

The modern focus on the homosexual nature of the intended crime is not shared by any biblical author. Ezekiel, for example, says the guilt of Sodom was that the city had “pride, excess of food, and prosperous ease” but failed to aid the poor and needy (Ezekiel 16:49). They were “haughty, and did abominable things” (16:50), but there is no specific indication that the “abominable things” were anything other than haughtiness and greed. In the New Testament, both Second Peter and Jude mention Sodom and Gomorrah, but neither one specifically mentions homosexuality in this context. Second Peter 2:4—10 connects these cities with “desire of what is unclean” (2 Peter 2:10), but does not specifically mention homosexuality. Jude 7 refers to “unnatural lust” at Sodom and Gomorrah, but this could refer to sex with animals, rape, or sex with anyone other than one’s spouse. Neither text mentions specifically the homosexual nature of the intended crime at Sodom.

While Israel’s law code did rule out sexual relations between people of the same sex (along with all forms of sexual activity other than between husband and wife), it is striking that the issue gets very little discussion in the Bible, and no biblical text offers a clear example of someone being punished for homosexual behavior. In the story of Sodom and Gomorrah, the problem is homosexual rape as a violation of hospitality.

The Birth of Isaac (Chapter 21)

In chapter 21 the long awaited child is born. By this time Abraham and Sarah are both very old, Sarah having already passed menopause (18:11). When the child is born (21:3) he is given the name Isaac (יִצְחָֽק). This name, built on the root word for laughter (צָחַק), is significant for two reasons. First, when the Lord appeared to Abraham and Sarah (chapters 17 and 18) both laughed at the possibility of bearing a child at such an advanced age (Abraham, 17:17; Sarah, 18:12—15). Here in chapter 21, though, Sarah interprets the name in a more positive light:

God has made me laugh. Everyone who hears it will laugh with me (Genesis 21:6 Palmer).

The “Sacrifice” of Isaac (Chapter 22)

In chapter 22 Abraham hears the voice of God telling him to sacrifice Isaac and offering no explanation. A paradox arises for the reader here. If Abraham kills Isaac, will he not destroy the only chance for fulfillment of the promise? If he does not kill Isaac, can the promise survive his lack of obedience? Abraham seems unbothered by this dilemma and sets out to perform the sacrifice. It is only when his willingness to follow God’s command is demonstrated that God prevents Isaac’s death.

| Read Genesis 22:1—19. | How does Abraham know that the voice of God is in fact the voice of God? Why does he not suspect that it is someone else speaking to him when the voice asks him to kill his own son? Be prepared to discuss this in class. |

|---|

The point of the story is clear enough: God tested Abraham’s faithfulness, and Abraham passed the test with ease. But upon further reflection, this story has raised troubling questions about the kind of faith that Abraham exercises here. Imagine that you meet someone who says God has told him to kill his child. Would you accept that as likely true or would you think the person was insane? Would you call the police? This, of course, is not the point of the biblical story, but this is a story that has raised this disturbing question for many readers.

In the biblical story Abraham does not end up killing Isaac. “The Angel of the Lord” steps in at the last minute to prevent it (22:11—12). The “sacrifice” of Isaac makes Abraham’s devotion to God absolutely clear. The story contributes greatly to the reader’s understanding of Abraham’s character. But we should not oversimplify the implications of the story. Abraham’s devotion does not imply a lack of initiative or an unwillingness to challenge God. In 18:22—33, for example, Abraham challenges God’s plan de destroy Sodom and Gomorrah and bargains for the salvation of their people (See the discussion above).

The Character of Sarah

In these same narratives (beginning in chapter 16) the author develops the character of Sarai/Sarah as well as that of Abram/Abraham. When faced with the long delay in the fulfillment of God’s promise, Sarah offers her servant girl, Hagar to Abraham as a surrogate. Hagar will bear the child, and Sarah will claim it.

While this story can be interpreted as illustrating a lack of faith, it can just as well be read as emphasizing Sarah’s strength and humility (16:1—3). She trusted that the promise would be fulfilled, but was willing to accept that it might not be fulfilled through her. The “solution” she proposes sounds terrible according to todays moral sensibilities, but this kind of surrogate motherhood was not unknown in the area and at the time this story is set.

Still, when Hagar conceives, Sarai becomes jealous and treats her harshly (16:4—6). At this point Hagar becomes the central focus of the narrative.

Hagar and the Naming God (16:7—16)

The angel of the Lord appears to Hagar in her time of distress after Sarai has dealt harshly with her. Hagar then names the Lord (16:7—14). She gives him the name El-Roi (which means “God of seeing,” or “God who sees,” or even “the God I see.” The narrative presents Hagar as both the one seen by God and the one who sees God. Note the name given to the place in 16:14.).

So she named the Lord who spoke to her, “You are El-Roi….” (16:13 Palmer).

Hagar is the only character in the entire Bible allowed to give a new name to God. What does it imply about the nature of Israel’s God that a servant girl is allowed to do what no one else is allowed?

The angel of the Lord tells Hagar that she is to name her child Ishmael (16:11). When the child is born Abram does as Hagar was told, giving the child the name Ishmael (16:15). This name, like El Roi emphasized something about God’s character. Ishmael means God hears.

This story, in which Hagar gives a new name to God (Genesis 16), comes before the stories in which God gives new names to Abram and Sarai (Genesis 17). It opens the sequence of naming stories that lie at the thematic center of the narrative of Israel’s ancestors.

Weaknesses of the Ancestors Are Acknowledged

While the positive attributes of Israel’s ancestors dominate the story, their weaknesses are not hidden from the reader. Abraham is afraid and tries to deceive the Egyptians by having Sarai claim to be his sister rather than his wife (12:11—13), and she is “taken into Pharaoh’s house.” Abraham demonstrates a striking lack of faith, and comes off looking ridiculous when Pharaoh discovers the problem. Sarah lies to the Lord, rather than accept that she has laughed at the promise (18:12—15). Her attempt to overcome the delay in the promise ends in ruin, with relationships within the family damaged (16:4—6).

It is unusual for such unflattering details to be included in ancient literature about the origins of a culture. Their presence here strengthens the narrative by making the characters seem credible. Sarah and Abraham seem more real than they would without these unflattering details.

The Isaac & Rebekah/Jacob & Rachel Cycle (Chapters 24—36)

In chapters 24—36 stories about Abraham’s son, Isaac are intertwined with ones about Isaac’s own son, Jacob. The promise is repeated to each of them (Isaac, 26:2—5, 24; Jacob 28:13—14).

Isaac parallels Abraham and Rebekah parallels Sarah in many ways, with stories told about Isaac and Rebekah closely resembling similar stories about Abraham and Sarah. Rebekah is barren (25:21), for example, just as Sarah had been (11:30), and Isaac lies about Rebekah being his wife (26:6—11) just as Abraham had done about Sarah (12:10—20; see also 20:1—18, where Abraham insists that Sarah really is his sister, but it was still untrue to imply that she was not his wife).

The Marriage of Isaac and Rebekah (Chapter 24)

The stories of Isaac and Rebekah begin in chapter 24, with Abraham’s concern to find a wife for his son. He is unwilling for Isaac to marry one of the Canaanite women where he now lives, so he sends a servant to make the long journey back to Haran to find a wife from among his own people (24:2—4).

| Find the region of Canaan and the city of Haran on the map of Abraham’s journeys above. |

Notice the tremendous distance from which Rebekah is brought to marry Isaac. The practice of bringing wives from long distances would create obvious difficulties for widows and divorced women. How could they return to their previous families? For this reason Israel’s legal code would later incorporate certain protections for such women that were undoubtedly a part of Hebrew nomadic culture out of which that legal tradition arose. We will return to this issue later in our discussion of Exodus—Deuteronomy.

Notice the subtle connection with the Hagar story: Isaac was coming from Beer-lahai-roi, the place where Hagar named God, when Abraham’s servant returned with Rebekah (24:62, compare 16:13—14). In the cycle of stories about Isaac and Rebekah, it is Rebekah who will be the strong character, with Isaac playing a much more passive role.

Conflict (Chapters 25—27)

Like Sarah before her, Rebekah is said to be barren (25:21), but she eventually has twins after Isaac prays for her. While she is pregnant God speaks to her and tells her that the elder son (Esau) will serve the younger (Jacob) (25:23).

And the Lord said to her,

“Two nations are in your womb,

two peoples born of you will be divided;

one will be stronger than the other,

the older will serve the younger” (25:23 Palmer)

| “Jacob” (יַעֲקֹ֑ב) means heel. The term is related to a verb (עָקַב) meaning attack from behind or supplant. Because of this connection, the name is sometimes taken to mean trickster. In the narrative Jacob certainly does play the role of a trickster. |

The struggle between Rebekah’s two sons becomes the frame for this entire section of Genesis. The foretold conflict begins even before birth as the two boys struggle with each other in their mother’s womb (25:22). At birth the struggle continues as Jacob grabs his older brother’s heel (25:26). Eventually Esau sells his birthright (inheritance) to his younger brother (25:29—34), and Jacob deceives his father on his deathbed and steals his older brother’s blessing (27:1—29). The division between the brothers is mirrored in the parents: Isaac loved Esau, while Rebekah loved Jacob (25:28).

In this narrative Rebekah is presented as a strong personality, determined to insure that what she believes to be God’s will comes about. It is at her suggestion that Jacob (the younger brother) “buys” Esau’s birthright and deceives Isaac in order to get the family blessing. Jacob is presented as a crafty trickster whose deceptions ironically lead to what God wanted.

Flight (27:41—28:5)

Jacob is forced to flee from Esau, and goes to the land of his uncle Laban (28:1ff). This begins a long travel section (28:1—33:20) through which the trickster (Jacob) is transformed. Unlike Abraham, whose travels are the story of a person of faith, Jacob’s travels are the story of a deceiver who is eventually changed by the Lord’s constant loving care.

Encounter (Dream) at Beth-el (28:10—22)

Jacob encounters the Lord in a dream at a place he names Bethel (House of God: 28:10—22). Here the Lord repeats to him the promise he had made to Abraham. Unlike Abraham, however, Jacob does not respond with unconditional faith. He agrees to serve God on the condition that God will take care of him (28:20).

Time with Laban (29—30)

The time which Jacob spends with Laban is a time of testing. The deceiver (Jacob) becomes the deceived, as Laban tricks him into marrying his older daughter, Leah (cow) when he had asked for the younger daughter, Rachel (ewe). Jacob serves Laban for seven years to gain the right to marry his daughter, then is given Leah instead of Rachel. He has to agree to work another seven years to get Rachel as well.

The Lord has compassion on Leah because she is unloved: “When the Lord saw that Leah was unloved, he opened her womb; but Rachel was barren” (29:31). To deal with her barrenness Rachel would employ the same strategy that Sarah had, giving her maid Bilhah to her husband to bear her a child (30:1—8). Leah would later do the same, giving her servant Zilpah to Jacob (30:9—13).

In spite of having to serve Laban for fourteen years, Jacob becomes wealthy. The narrative does not clearly indicate whether his gain comes from the Lord or his own resourcefulness (See 30:25—43). Still, in the end it all works out to be within the scope of God’s will.

Flight toward Home (31—32)

Eventually, Jacob finds himself needing to flee from Laban because of the jealousy of Laban’s sons and return to his homeland (31:1—3), and Rachel steals Laban’s household idols (31:19), causing him to chase after Jacob(31:22—35). The return trip (flight) matches scene-for-scene (but in reverse order) the stopping points on Jacob’s original journey to Laban’s house.

The conflict with Esau has still not been resolved, and as Jacob travels home he sends gifts to appease his brother’s anger (32:3—5). But Jacob’s messengers return to him saying that Esau has set out with four hundred men to meet Jacob. Jacob becomes very afraid. He reaches the climax of his inner journey through the resolution of this perceived crisis. Notice how Jacob has changed. Compare his prayer in 32:9—12 (especially verse 10) with his earlier attitude at Bethel (28:20—22).

Struggle at the River Jabbok (32:22—32)

When he reaches the Jabbok River, he sends his family on across and remains behind, spending the night struggling with a man who is not identified (32:22—32). The fight is a draw, and the man asks Jacob to let him go, but Jacob refuses, saying he will not release him until the man blesses him. He gets the blessing, along with a change of name to Israel, and a wounded hip.

The new name can mean either one who struggles with God, or God struggles. The scene becomes symbolic of the way Jacob relates to God. His relationship with God is a deal to be negotiated, not a life of trust in God’s grace. He struggles with God, and God must struggle with him. Still, God does not abandon him but honors the promise.

Reunion with Esau (33:1—17)

When Jacob and Esau finally meet, Esau runs to Jacob, embraces him, and kisses him (33:4). The two brothers weep. Jacob is overcome by Esau’s welcome and says to him, “to see your face is like seeing the face of God, since you have received me with such favor” (33:10). Jacob seems to have come to understand that life with God is not a deal to be negotiated, but grace to be accepted.

A Second Encounter at Beth-el (35:1—15)

Jacob returns to Bethel, where again he encounters God. God once again changes his name to Israel (35:5—15), confirming that the “man” with whom Jacob had struggled did indeed speak the voice of God, and reaffirming the change that has resulted from Jacob’s long struggle.

Birth of Benjamin/Death of Rachel (35:16—21)

Rachel dies in childbirth. As she dies she names her newborn son Ben-oni (בֶּן־אוֹנִ֑י, Son of my sorrow), but Jacob called him Benjamin (בִנְיָמִֽין, Son of the right hand, or Son of the south). Note the symbolism of the right hand, the hand of blessing. It will become significant later in the Joseph cycle. Blessing is another significant theme throughout the ancestor stories. Isaac was the second son of Abraham. Jacob was the second son of Isaac and Rebekah. Benjamin is the second son of Rachel. Each of these second sons is blessed.

Death of Isaac and Reconciliation of Jacob and Esau

(35:27—29)

Isaac, who was on his deathbed when the conflict began, finally dies after his two sons are reconciled. While the narrator does not assert it directly, the narrative strongly implies that Isaac was waiting to see this reconciliation.

The story of Jacob—later called Israel—is the story of a person who finds faith only by seeing God in his brother’s compassion. Faith does not come easily for Jacob, but his life journey leads him eventually to it.

Israel and Edom: the Genealogies of Genesis 36

In chapter thirty six the narrative is again punctuated by a collection of genealogical data. The purpose of this toledot is to establish the relationship of the nation of Edom to Israel. The chapter seems to include elements from several older lists, combined here to assert that the Edomites are descendants of Jacob’s brother, Esau.

| Before any king ruled over the Israelites | Chapter 36 includes a list of the kings who ruled in Edom “before any king ruled over the Israelites” (36:31—39). What does this imply about the time the text was written? Would the author have written this phrase if he were writing before there were kings in Israel? |

|---|

The final section of the book of Genesis (chapters 37-50) focus on Rachel’s oldest son, Joseph. The link below (when activated) will take you to the discussion of that material.

Further reading on the Book of Genesis:

- The Joseph Cycle (37—50)

Terms and Concepts to Remember

| Abram/Abraham | Father of the nation of Israel. Husband of Sarai/Sarah and father of Ishmael and Isaac. Abram means “Great Father.” Abraham means “Father of many.” |

|---|---|

| Bethel | |

| El Elyon | A name of God usually translated as “God Most High” |

| El Roi | A name of God translated as “God who sees” or “God of seeing.” According to Genesis 16:13, this name was given to God by Hagar, the slave of Sarah. |

| El Shaddai | A name of God often translated as “God Almighty,” but sometimes more literally rendered as “God of the Mountain” |

| Eponymous | |

| Etiological | Having to do with causes and origins. An etiological story is one that attempts to explain why something is as it is. |

| Jacob/Israel | The “trickster” who outwitted his older brother Esau. Son of Isaac. Grandson of Abraham. Husband of Leah and Rachel. Namesake of the nation of Israel. |

| Rebekah | Wife of Isaac. Mother of Esau and Jacob. A courageous woman who intervened to insure the fulfillment of God’s promise to her. |

| Rachel | |

| Saga | A long story following the lives of one family from the distant past over several generations |

| Sarai/Sarah | Wife of Abram/Abraham. Mother of Isaac. Sarah is a character with a strong sense of realism and humility. |

| Shem | A Hebrew word meaning name, reputation, glory. This is also the name of Noah’s first son. The word is important for understanding the Tower of Babel story (Genesis 11:1—9). |

| Toledot | A Hebrew word often translated as generations or descendants but more clearly rendered in some contexts as results or what came of this |