We do not know exactly how all the writings in the Bible came to be assembled in one volume, but there is clear evidence that the books contained in the Bible originally circulated independently, and only after a long process that we call canonization were they gathered together into a single volume treated as canon. The term canon means an official list of writings treated by a community as its authority.

2 Kings 22 and Chronicles 34 relate the story of a female prophet named Huldah who is said to have authenticated an early version “the Law”, perhaps an early edition of the book of Deuteronomy. That would place the beginning of the process of canonization as early as the 600s BCE.

By the fifth century BCE (400 BCE) the Torah was widely accepted as scripture. By the first century CE it was likely considered canon by all Jewish communities. Most of these communities had accepted the Prophets as scripture by about 200 BCE, and all of the New Testament writers clearly accept them as such, but the Sadducees, a group with which Jesus had frequent contact (and more than a little conflict), probably accepted nothing outside the Torah as scripture. The Pharisees, on the other hand, regularly cited the Prophets, the Writings and even the oral tradition of the elders with the authority of scripture. That oral tradition would later be gathered together in written form as the Mishnah.

Around 100 CE canonization of the Hebrew Bible was complete, with the Torah, the Prophets, and the Writings all clearly accepted as scripture by all forms of early Judaism. This process was not without debate. In the years leading up to the time of Jesus, for example, Jews in Egypt produced a Greek translation of the Hebrew scriptures and used a different order for the books of the Prophets and the Writings than the order later accepted as canon by the larger Jewish community in Israel. They also used several books that were later rejected by Jews elsewhere. This Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible became known as the Septuagint because of the legend that it had been produced by seventy (or seventy two) scholars working independently but producing identical translations.

The order of the Prophets and the Writings used in the Septuagint became the standard for the Christian community, and the additional books continued to be used by many Christians even after they were rejected within early Judaism. (In fact, these extra books may still be found in Catholic and Orthodox Bibles.) Protestants have retained the order of the Septuagint, but use only the books found in the Tanak accepted as scripture by the larger Jewish community.

The New Testament writers—all of whom wrote in Greek—tend to follow the wording of the Septuagint where it differs from the Hebrew Tanak. Still, with only one exception, they quote only from those books of the Septuagint that are translations of ones now accepted as part of the Hebrew Tanak.

Within Christian communities about 90 CE someone (we don’t know who) collected copies of Paul’s letters from the churches he had served and put them all together into a single unit. Gradually, the Gospels, Acts, and other documents were added to this collection.

The Gospels, Acts, and Paul’s letters were probably widely known and used for teaching by the early to mid second century CE (100-150 CE). All of them were written before the year 100 CE. It took much longer, however, for a complete list of New Testament documents to be established. The specific books that did make it into the canon did so through long-term and widespread use in the Christian community. Canonization was a lengthy process of usage and habit, not the result of any act or decree of the church. (Church decrees came later).

Why did the early Christian communities decide that it was important for all Christians to agree on the contents of the New Testament? Why not just allow each church to judge which documents it should use? This, of course, was the practice at first. Some churches had copies of all of Paul’s letters and one of the Gospels. Another church might have five of Paul’s letters and two Gospels. Why not let this situation continue?

The Marcionite Crisis

A crisis arose in the middle of the second century CE, and large numbers of Christians began to realize that unless they agreed on the contents of the Christian canon they would not be able to prevent similar crises in the future. This one crisis was clearly not the only factor that led to closing the canon, but it illustrates well the problem that an open canon posed.

Up to the 2nd century the Bible used by Christians consisted mostly of the Septuagint and—at least in some locations—one or more of the Gospels and the collected letters of Paul. About 140 CE a Roman Christian named Marcion said that Christians should discard the whole Old Testament. Marcion proposed that only his edited version of the Gospel of Luke and Paul’s letters should be accepted as scripture. Of course, this proposal produced strong conflict within the church.

Marcion was not a gnostic philosopher, but some of his views align well with what has come to be called gnosticism (Greek: gnosis = knowledge). From a gnostic perspective, right relationship with the divine depended on attaining a certain ‘knowledge’ of spiritual truths. Reality was viewed as divided into two modes of being: the spirit realm, which is good, and an inferior physical realm which is inherently evil. The human spirit belonged to the good spirit realm, while the body with its desires belonged to the evil realm of physical matter.

Marcion concluded from this reasoning that there must be two Gods, since a good God—the Father of the Christ—could never have created the inherently evil physical world. There must be an evil creator God, Marcion thought. He reasoned that the Hebrew Bible, beginning with the words “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth”, must be about the evil creator God, and therefore should not be read by Christians. Any supposedly Christian literature that spoke too approvingly of the Hebrew Bible must also be rejected, he thought. After deleting certain passages from Luke’s Gospel and the letters of Paul, he presented these edited versions as the only Christian scriptures.

Recognition of the Need for Agreement

While canonization of Christian writings had begun long before Marcion (note the collection of Paul’s letters by about 90 CE), Marcion’s views helped emphasize the urgent need for deciding the question of what scripture should include. How could the Christian community respond to wild theologies like that of Marcion if it had no agreement on what counted as scripture? How could Christians argue that Marcion was wrong in his suggestion that they only read Luke and Paul? They could answer people like Marcion only if they had a prior agreement on which documents really had the status of scripture.

After Marcion was expelled from the church in 140 CE and his teachings were condemned as heresy, his influence lingered for some time. Many early Christians believed Marcion and left the church with him. This led to the first major split in the Christian movement. Church leaders were forced to respond to his teachings. They began to publicly defend other christian documents as authoritative besides the Gospel of Luke and Paul’s letters.

Empirical Evidence for the Growth of the Canon

If you were asked to write a research paper to test whether the dates given in section II above were correct, what kind of evidence would you try to find? What would count as evidence that a particular document was considered scripture at a particular point in time?

A small amount of evidence may be found in the New Testament itself. 2 Peter 3:15-16 indicates that by the time of writing of the latest New Testament documents Paul’s letters had been accorded the status of Scripture by at least one important segment of the early Christian community. At least three other kinds of evidence have helped scholars answer the crucial questions surrounding canonization.

Comments by Early Church Leaders

A number of the leaders of the early church in the second and third centuries, commonly called the Church Fathers, made comments about whether they considered a particular document to be scripture. We still have some of their writings, and these comments provide valuable evidence for reconstructing the veiws of the early churches on the issue of the canon.

The first reference to one of the Gospels as scripture occurs in a letter which scholars call 2 Clement (early 2nd century CE). Justin Martyr, a few decades later, also refers to the Gospels as though they had authority equal to that of the Hebrew Bible (though he does not call them “Gospels”, and we cannot be 100 percent sure that he was referring to the exact documents that we now use).

Early Canon Lists

In at least three cases, someone in the early church made a list of what she or he considered to be scripture and sometimes even offered an explanation for why each document should be accepted. These lists demonstrate the diversity of views in the early churches. They usually contained the four Gospels, Acts, and Paul’s letters, but beyond that they vary greatly.

The Muratorian Canon is an early list dating from some time between the end of 2nd century and the early 4th. It lists the following items and gives arguments supporting each one. (The items in boldface type are not found in present day New Testaments.)

| 4 Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) Acts 13 letters of Paul Jude |

1 Peter (but not 2 Peter) Wisdom of Solomon Revelation Apocalypse of Peter |

Codex Claromontanus is a sixth century copy of the Pauline epistles plus the letter to the Hebrews in Greek and Latin. An early canon list, dating from the fourth or early fifth CE, was inserted between the letter to Philemon and the one to the Hebrews in this manuscript. That list includes four books as scripture which would later be rejected as non-canonical.

| Books included in the Codex Claromontanus list, but later rejected | |

| The Epistle of Barnabas The Shepherd of Hermas |

The Acts of Paul The Revelation of Peter |

Other than these four books, however, the list in Codex Claromontanus agrees substantially with the present list of contents for the New Testament.

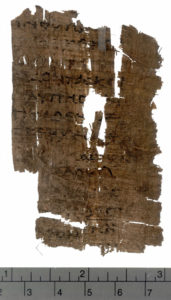

Ancient Copies of the Bible

Finally, we have many ancient copies of the Bible that can serve as valuable evidence. A number of these Bibles contain books that are no longer in the Bible today. Others are missing some books that are used today.

Codex Alexandrinus (5th century CE), for example, contains both 1 and 2 Clement as part of the NT. While 1 Clement is a letter written about 96 CE by a historical bishop of Rome, 2 Clement is a pseudonymous document written later.

Comments by early Church leaders, early canon lists, and ancient copies of the Bible all provide evidence suggesting that canonization of the New Testament involved a long process of debate, with a consensus arising only after several centuries of the Church’s experience with these documents.

Books Accepted Late

The Revelation to John, Hebrews, and several of the Catholic Epistles (2 Peter, James, 1, 2, and 3 John, and Jude) took much longer to be accepted into the Canon than did the other books. Even the Gospel of John was resisted by some of the early churches since some parts of it seemed to them to support gnostic teachings.

The Definitive List

Two events helped resolve the debate over the canon. First, Athanasius’ Easter letter (367 CE, discussed above) had tremendous influence. Athanasius was a respected church leader, and his views on this topic seemed compelling to many other church leaders who came after him. Second, Jerome’s translation of the Bible into Latin (4th century CE), knowns as the Vulgate Bible, soon became the standard for the Latin-speaking churches, and Jerome followed Athanasius list.

Concluding Summary

Each of the books of the Bible originated separately and at first circulated independently of the others. They were gradually gathered together into a single collection and gained the status of scripture through longterm use in the churches.

Canonization served at least two main purposes: it helped clarify acceptable Christian belief, and it gave a certain level of unity to the diverse churches spread over the vast Roman Empire.

Related Pages:

Some Key Terms

Look at the following lists of terms. Can you say what each one means? Some appear in boldface type within the chapters you have already read. Others appear for the first time in this chapter.

| Canon Hebrew Bible Torah Prophets Writings Covenant Testament |

Apocrypha Deuterocanon Scroll Codex Diaspora Pseudepigrapha Septuagint (LXX) |

| Dead Sea Scrolls Qumran Essenes Athanasias of Alexandria 367 CE The Gospel of Thomas |

Catholic Epistles Pseudonymity Eusebius Marcion Vulgate Bible |

Image Credit: The image at the top of this page has been released into the public domain by the photographer. It shows a statue of Athanasius of Alexandria created by Carl Rohl Smith, 1883-84. The statue is located at Frederikskirken, København. The image shown here is adapted from Wikipedia Commons.