The vast majority of contemporary Jews and Christians do not read Classical Hebrew or Ancient Greek, so the biblical documents have been translated into many different languages. Long before there were translations of the Bible into English, Christian and Jewish scholars had produced translations of the Hebrew Bible in languages such as Greek, Latin, and Syriac. After examining a few of these early translations we will look at the first translations into English, then address a number of issues related to more recent translations of the biblical texts.

Here are a few terms, names, and dates that will appear in this discussion:

| Venerable Bede (730s CE) Jerome (c. 374-419 CE) John Wycliffe (1384 CE) 1455 CE 1517 CE |

William Tyndale (1525) King James Version Authorized Version (1611) |

The Septuagint Bible (LXX)

The earliest known translation of the Hebrew Bible is often called the Septuagint. The Septuagint is a translation into the common Greek of the Eastern half of the Roman Empire. It was produced by Jewish scholars in Egypt, but became particularly influential for the early Christian missionary movement since most of the earliest missionary work (including all of Paul’s journeys) took place in Greek-speaking areas.

The term Septuagint comes from the Greek word for seventy. The legend that circulated widely about the origins of the Septuagint—but which is certainly exaggerated—claimed that this translation was produced by seventy (or seventy two) scholars working independently. According to the legend they all produced identical translations. Because of this legend, the common abbreviation for the Septuagint is the Roman numeral LXX (seventy).

The Septuagint is significantly different at many points from the Hebrew text we now have for the Old Testament. This could mean either that it is a particularly sloppy translation or that it is based on a Hebrew original which was itself different from the Hebrew text known today.

The LXX and the New Testament continued to circulate in Greek in the eastern half of the Roman Empire for several centuries. In the west, however, the dominant language was Latin. Translations of the NT into Latin began to appear early. This process culminated in the production of the Latin Vulgate translation.

The Latin Vulgate

The Latin Vulgate translation, which remains the official Bible of the Catholic Church, was produced by Jerome (c. 374-419 CE). The Roman Empire collapsed in the late fifth century (400’s) under the weight of barbarian invasions. During the Dark Ages of the early Medieval period, new European languages began to appear. Latin remained the official language of the Roman church, however, and no major new translations appeared for nearly 1000 years.

Early English Translations

Translations of the Bible into English began to appear over 1000 years ago, but the English of those translations was so different from the English that we speak today that you would hardly recognize a word of them.

Early English Translations of the Vulgate Bible

Even during the middle ages a few people did attempt to translate the Bible into one of the new European languages. The first credited with doing so was the Venerable Bede, a Benedictine monk and historian of Anglo-Saxon England. In the 730s he rendered part of Jerome’s Latin Vulgate into Old English. If you could see a copy of Bede’s work you would not recognize it as English.

Not until the 14th century did the entire Bible become available in English. John Wycliffe finished his translation in about 1384. The national church, however, feared the consequences of the Bible being read and interpreted by laypersons. Wycliffe’s translation was condemned in 1408 and the church forbade any further translations.

The Printing Press and the Protestant Reformation

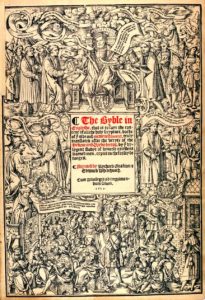

Johann Gutenberg‘s invention of the printing press in 1455 made the production of bibles much easier. This fact, together with a movement called the Protestant Reformation, insured that the Bible would at last become available to a larger reading public in English.

The Protestant Reformation began in Germany in 1517. A German priest named Martin Luther strongly protested corruption in the Roman Catholic Church. His German translation of the Bible in 1522-1534 was the first translation in a modern European language based on Hebrew and Greek texts rather than the Latin Vulgate. It served to increase the desire for an English translation made in the same way.

English Translations from the Greek and Hebrew Texts

The first English translator to work directly with the Greek and Hebrew manuscripts was William Tyndale. His English translation of the NT was published in Germany in 1525 (later revised in 1534). Though Tyndale’s work was done well after the invention of the printing press, it was produced by hand since he could not afford the cost of printing. Tyndale was eventually burned at the stake for his work.

The first printed English Bible (the Coverdale Bible) appeared in 1535, only one year after the revised edition of Tyndale’s Bible. While the church forbade the reading of Wycliffe’s and Tyndale’s translations, it permitted the distribution of the Coverdale Bible, which relied heavily on Tyndale’s work.

Matthew’s Bible (1537), which contained additional sections of Tyndale’s OT, was revised by Coverdale and the result was called the Great Bible (1539).

The Bishop’s Bible (1568) was a revision of the Great Bible. The Geneva Bible (1560), was produced by English Puritans in Switzerland a few years before the appearance of the Bishop’s Bible.

From this rapid overview of early English translations from the Greek and Hebrew texts you can see that in the period between 1525 and 1611 many new translations of the Bible appeared in English. The King James Version was the latest in this wave of translation work.

The King James Bible

The King James Version (1611) was the last in a rapid succession of translations produced between 1525 and 1611. James I, son of Mary, Queen of Scots, appointed 54 scholars to make a new version of the Bishop’s Bible for official use in the English (Anglican) Church. After 7 years labor, during which time they consulted the oldest manuscripts then available, they produced the King James Version, also called the Authorized Version in 1611.

At first many English readers were skeptical about the new translation, but in time it won the favor of the public and eventually put most of the other English translations out of print. Its tremendous popularity can be explained by two factors. First, it was a much more polished literary production than most of its predecesors. Second, it was a very carefully done translation which made significant improvements on the accuracy of earlier editions.

English Translations of the Bible in the Last Fifty Years

In the past fifty years a large number of new translations of the bible into English have appeared. What explains this renewed surge in translation work, and why do these recent translations differ so much from one another?

The English language has changed significantly since 1611. A quick perusal of the following lines from the King James Version should make this clear:

- Psalm 59:10 The God of my mercy shall prevent me: God shall let me see my desire upon mine enemies.

- Psalm 79:8 O remember not against us former iniquities: let thy tender mercies speedily prevent us: for we are brought very low.

- Psalm 88:13 But unto thee have I cried, O LORD; and in the morning shall my prayer prevent thee.

- Psalm 119:148 Mine eyes prevent the night watches, that I might meditate in thy word.

- Amos 9:10 All the sinners of my people shall die by the sword, which say, The evil shall not overtake nor prevent us.

- 1Th. 4:15 For this we say unto you by the word of the Lord, that we which are alive and remain unto the coming of the Lord shall not prevent them which are asleep.

Would you read these texts differently if you knew that in 1611 the word “prevent” did not mean “stop someone from doing something” but “come before” or “come into the presence of”? In some cases this knowledge could make a tremendous difference.

Second, we need more recent translations because we can do a far more accurate job today of reconstructing the exact wording of the original text than was possible in 1611 (See Manuscripts and Transmission). In 1611 the translators of the KJV had at their disposal only a handful of manuscripts for some portions of the Bible. Today we have hundreds of manuscripts for some of those same texts.

Differences between Contemporary Translations

There are two main reasons that modern translations of the Bible differ so much from one another. First, the translators must decide which manuscripts to translate. Different decisions lead to different translations. Second, even if they agree on the proper manuscripts, they may differ on how they believe a good translation must be produced. They may have different translation theories. Let’s examine a few key issues about translation theory, then we will look briefly at the question of manuscripts.

A translation is a statement in one language of something originally stated in another. Imagine that I started class on the first day of a new term by saying to my students: “Buenas tardes, alumnos. Me llamo Micheal Palmer. Soy su profesor de la historia y literatura de la biblia. Vamos a estudiar la historia cultural, sociológica, y política de la época de los documentos bíblicos.” You would need a translation if you don’t speak Spanish. A translator would have to first decide what I meant, then say something in English which means as close to the same thing as possible. [By the way, the what I meant when I wrote those Spanish statements can be roughly presented in English as, “Good afternoon, students. I’m Micheal Palmer. I’m your “History & Literature of the Bible” professor. We’re going to study the cultural, sociological, and political history of the times of the biblical documents.“]

To produce a translation of the Bible, a a translator or group of translators start with the text of the Bible in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek and restate in English what they believed it to mean.

All of the versions of the Bible now available in English involve paraphrasing to one extent or another. A paraphrase is a restatement of a message, usually for the sake of clarity, using different words. For example, let’s imagine that you said to me, “I won’t be in class next Tuesday.” I could related this information to someone else in several different ways. I could say, “She said, ‘I won’t be in class next Tuesday.'” That would be a direct quote. On the other hand, I could say something like, “She said she wouldn’t be in class next Tuesday.” That’s not a direct quote, but it is a good paraphrase. It accurately represents what you said, but uses slightly different words to do it.

There is an important sense in which every translation must involve paraphrasing. It would be impossible to translate a message from one language into another and use exactly the same words. No word in Greek or Hebrew means exactly the same thing as any word in English. No word in English means exactly the same thing as any word in even a closely related language like Spanish (though some are deceptively close). Even if all the words of Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek did have exact matches in English (and they don’t), the grammar of these languages is different from the grammar of English. The order of words in a sentence is different from one language to another. Some words, such as the verb “is” in the sentence “Mary is tall” are required in English, but not in Greek, so they have to be added to make an English translation understandable. Because of these differences it is impossible to translate from Greek and Hebrew into English without paraphrasing.

Some translations of the Bible were produced by translators who tried to be as literal as possible. Whenever possible, they used one English word to represent each Greek, Hebrew, or Aramaic word. Many scholars now feel that these translations have led to serious misunderstandings of some biblical texts. Some good examples of extremely literaltranslations are the King James Version, the Revised Standard Version, and the New American Standard Version. The New Revised Standard Version is also literal, but slightly less so than these.

The positive contribution of these literal translations is that they sometimes let the serious Bible student see something of the structure of the text in the original language, but they can also be deceptive in this regard as well. There is really no substitute for reading the text in the original language. No English translation can provide direct access to the structure of the Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic texts.

Other translations have been produced by people who, recognizing the inherent problems involved in overly literal translations, have attempted to translate the meaning of the biblical texts without much concern for how many English words it takes to do so. These translators have attempted to produce more accurate translations by being less literal. They have attempted to translate meaning-for meaning rather than word-for-word. Some common examples of non-literal translations are the New International Version, the Today’s English Version (Good News Bible), the Contemporary English Version, and the Revised English Bible.

All translations depend on the ability of the translator to correctly understand the literary and historical contexts in which each statement in scripture was written and how each statement fits into the larger passage around it. Subjectivity is a natural part of this process.

Many readers find it helpful to compare several different translations of the Bible. Reading both a literal and a non-literal translation can be particularly instructive. Read both and see how they differ, and ask yourself what the differences indicate about the way the translator understood the passage you read.

Another factor influencing Bible translations is the particular manuscripts (hand-written copies) of the Bible the translator(s) used (See Manuscripts and Transmission). Translators must decide which copies to translate. Some of the differences between the modern English translations stem from the fact that the translators used slightly different manuscripts. Many of the oldest and most reliable copies we now have were not available when the King James Version was written, for example. Many of the more recent translations are based on these more reliable manuscripts.

If understanding the biblical texts is highly important to you, you should consider studying at least one of the biblical languages and taking a course in textual criticism.

Concluding Summary

The Bible has been translated into many languages, and has been translated into some of them multiple times as scholars have gained a better understanding of the form of the original texts and their meanings. Translation became necessary even before the birth of Jesus, and it has remained necessary as Christianity and Judaism have spread into new areas where other languages are used.

The King James Version was for many years the favorite translation of the Bible into English, but it was not the first.

The invention of the printing press made the publication of new translations easier, with the result that today we have multiple translations available to us in any of several of the world’s must used languages.