Today we spent some time discussing possible perspectives on John’s Gospel, speculating about what can be known historically about its origins, and reading the hymn to the logos (λόγος) in chapter one.

We looked at passages that strongly imply a growing separation between early Christianity and its Jewish roots. 1:17, 9:28, and 15:25 (“their law” rather than “our law”), for example, can easily be read to imply an incompatibility between Moses and Jesus. In this context, what does the author’s decision to begin this Gospel with a poetic discussion of the cosmic significance of the logos imply?

We read 1:1-5 twice, once looking at it as traditionally read, with λόγος referring to Jesus, the Christ, and once reading λόγος as “reason” as an early Greek stoic might have read it. How would the assertion in 1:14 that the word (logos) became flesh and lived among us sound to early Jewish readers? If we understand logos as a reference to divine “reason” rather than “word”, how might the assertion have sounded to Greek readers steeped in Stoic assumptions? The author’s assertion that “the λόγος became flesh and lived among us” (1:14) challenges some basic assumptions of both groups.

Feel free to join us next week as we continue to probe both the theological contributions of John’s Gospel and the problem of coming to terms with the violent anti-Jewish rhetoric that has claimed support from this same Gospel for centuries.

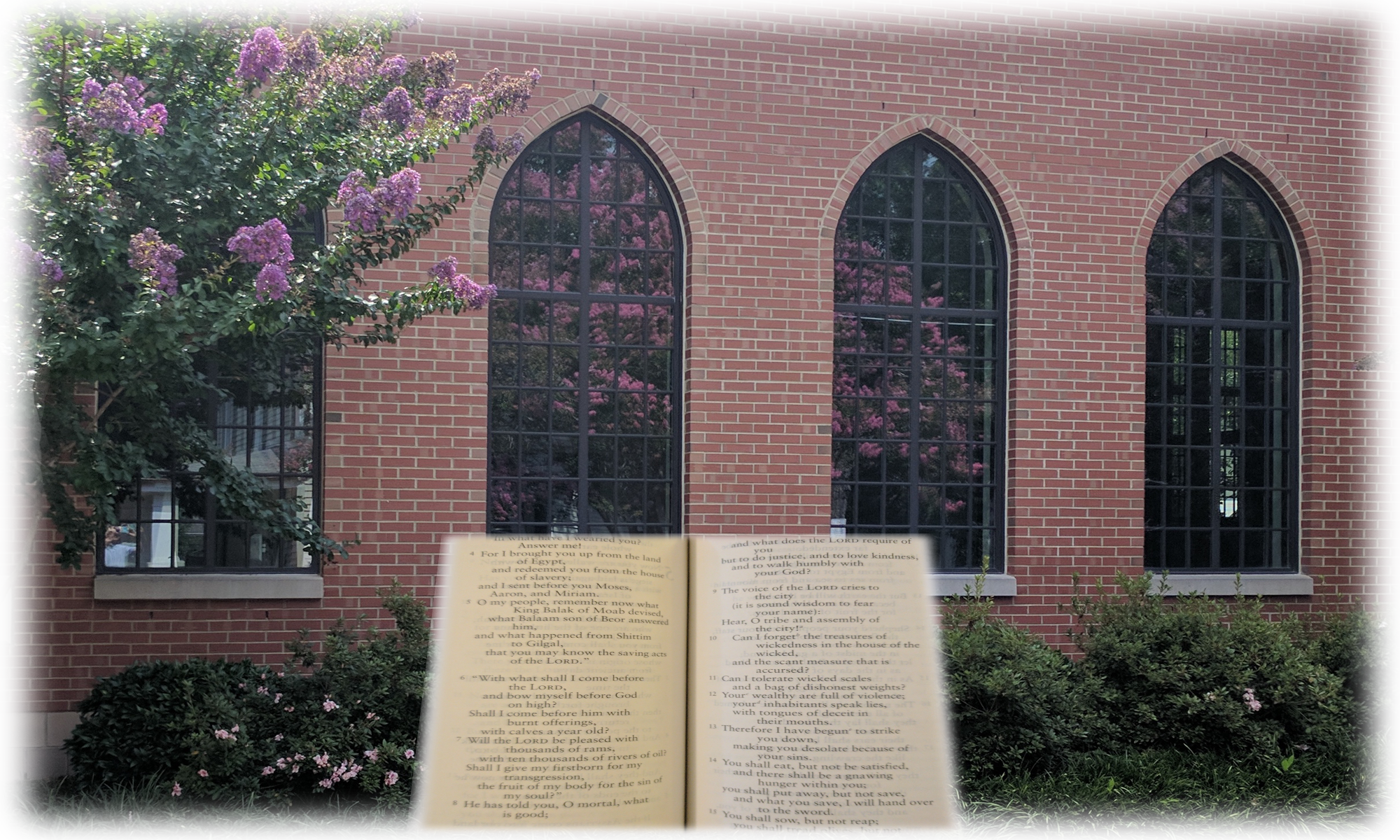

The image at the beginning of this post is one side of the oldest fragment of John’s Gospel. It begins and ends with the words οἱ Ἰυοθδαίοι, universally translated as “the Jews” in published English versions of John’s Gospel, though we will see later in this class that “the Jews” is not the only option for translating this phrase.

You must be logged in to post a comment.